Legendary French director’s thoughts on equally legendary Tour winner

Cyrille Guimard, the legendary directeur sportif, was a key influence in the early careers of the riders – Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond – whose battle for the 1986 Tour de France is at the heart of my new book, Slaying the Badger, writes Richard Moore.

Cyrille Guimard, the legendary directeur sportif, was a key influence in the early careers of the riders – Bernard Hinault and Greg LeMond – whose battle for the 1986 Tour de France is at the heart of my new book, Slaying the Badger, writes Richard Moore.

But Guimard was involved with neither at the time of the 1986 Tour, which LeMond and Hinault began as La Vie Claire teammates but became, as the race unfolded, bitter adversaries.

Watching his two former protégés line up together in La Vie Claire colours at the start of that 1986 Tour, Guimard now claims he knew there’d be trouble. His team, Système U, had a clear leader: Laurent Fignon. He thought the La Vie Claire arrangement, with two riders capable of winning the Tour, was a recipe for disaster; he simply didn’t believe it was possible to accommodate ‘two ten-point stags in the same herd of deer.’

It was why Guimard had been happy to see Hinault leave his team at the end of 1983, the year that Fignon emerged to win the first of his two Tours. And it explains why he could deal with LeMond departing for La Vie Claire a year later, when Fignon won his second Tour.

‘I realised very early on with Fignon and LeMond that I was going to have two bucks who would want to kill each other,’ as Guimard put it when he was interviewed for my book. ‘You can’t have two ten-point stags in the same herd of deer. You can’t trust it. It can only end in one thing: mortal combat.’

The following extract comes from early in the book, with Guimard discussing Hinault. He eventually fell out with ‘Le Blaireau’ (the Badger), but it’s clear that he remains an admirer of his talent, even going so far as to rank Hinault as the greatest ever.

As Guimard put it: ‘No one else has ever been in the frame with the Badger. Not even in the frame. [He was] above Merckx. The Badger had the greatest athletic potential of any rider ever. By far.’

—

Cyrille Guimard, wearing a freshly laundered white shirt, is sitting behind his desk in his unremarkable, spartan office. Next door is the Vélo Club Roubaix shop, and next to that the club bar, in a whitewashed outhouse attached to the famous Roubaix velodrome. On the breast of Guimard’s shirt is a logo, offering a clue as to his current occupation: he runs Équipe Roubaix-Lille Metropole, a third-tier professional team affiliated to VC Roubaix.

This could be considered quite a fall from grace for somebody acclaimed as one of the best directeurs sportifs ever to sit behind the wheel of a team car, and who, between 1976 and 1984, guided three different riders to no fewer than seven Tours de France – which is to say, every edition of the great race bar two. But in his haughty manner, and in the abrupt way he dismisses those who have taken a wrong turning in the club shop and wandered into his office by mistake, Guimard is not somebody who should be counted among those who now doubt his genius. Though his office is modest, the same should not be said of Guimard.

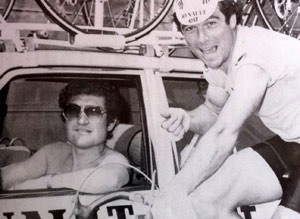

Perched on his distinctive large nose are his equally distinctive and large 1970s-style spectacles, with his greying mop of unruly hair giving him a vaguely professorial air (in his pomp as a directeur sportif, Guimard’s curly brown bouffant and trademark oversized aviator sunglasses gave him the appearance of a Boogie Nights-style 1970s porn star; these days, his hair is greyer and, though it still has plenty of ‘body’, straighter, as though the perm is growing out).

A few hours after our meeting, Guimard will begin his other job, commentating for French radio on the famous cobbled Classic Paris–Roubaix. But for now he is casting his sixty-three-year-old mind back thirty-five years, to his first encounter with Bernard Hinault. Or, rather, The Badger. It is an endearing curiosity that although these two proud Bretons worked together for the best part of a decade, Guimard rarely refers to his former protégé as ‘Bernard’, ‘Bernie’, or ‘Hinault.’ Throughout, he is simply ‘Le Blaireau’.

It is said not for comic effect – though Guimard has some funny lines – but with sincerity, and even respect. ‘The first time that I came across the Badger…I can’t remember,’ he says initially, searching his impressive mind. ‘Ah, si, si, si, it was the Étoile des Espoirs. He was riding for the French amateur team. I was third and he must have been fourth [in fact, he was fifth]. It must have been…’ Guimard turns to his computer, launches Google, and after several minutes and countless mouse-clicks, turns back: ‘1974! Yes, the Badger’s first year as a pro was my last.’

Guimard was a good rider – among over 100 wins were the French national championship and seven stages of the Tour – but it was as a directeur sportif that he achieved greatness, and for which he is best remembered today. Like Alex Ferguson, a trade union agitator before he became a footballer and then a great manager, Guimard demonstrated his leadership qualities early in his athletic career.

He was appointed president of the professional riders’ trade union, the Union Nationale des Coureurs Professionnels, when he was just twenty-three – the same age, coincidentally, at which Hinault would also demonstrate his ability to lead a group of dissatisfied workers in the riders’ strike at the 1978 Tour. But, again like Ferguson, it was as a manager that Guimard transcended his own gifts as a rider, his tactical and strategic genius combining to brilliant effect with his forceful, forthright personality. ‘Everything Guimard said at the briefing came true by the end of the race,’ said Lucien Van Impe, the Belgian climber whom Guimard led to the 1976 Tour, in his first year as a directeur. According to the cautious Van Impe, Guimard didn’t merely advise: he ordered him when to attack.

‘I already knew the Badger when he turned professional,’ says Guimard now, musing on his early impressions of the rider with whom he would forge such a close and mutually successful relationship, until a spectacular fall-out precipitated, in Hinault’s words, ‘three years of war’.

Guimard explains: ‘I’d followed his results in races in Brittany and I was in contact with the people who’d taken care of him around the time he did the Route de France. They’d asked my opinion about whether to pick him for the Route de France, and I’d said no.’ Typically, Guimard offers no elaboration. ‘But when I raced with him at the Étoile des Espoirs, that confirmed the impression I had of his physical potential.

‘In 1974 he must have been barely twenty, he was just out of the army, and I could see straight away that he was a cut above the others of his age,’ Guimard continues. ‘He could already generate enormous power. The only thing he wasn’t particularly advanced in was his racing strategy. You know, when you’re on a higher plane, you tend to rely on your strength a bit too much…Later on, he got better in that regard, even if his first line of defence was always his physical superiority.’ After his competitive encounter with Hinault in the Étoile des Espoirs, Guimard says he ‘could already see that we had a rider who could scale the highest peaks, without a shadow of a doubt.’

On Hinault’s physical ability, Guimard is absolutely certain: he was born with it, and to emphasise that fact, he twists his wrist as though opening the throttle on a motorbike. ‘The size of the motor is written in the genes,’ says Guimard. But in the matter of his mindset, of his formidable mental strength, of his ability to lead and the raw aggression he used to such devastating effect in so many races, Guimard is more circumspect. ‘You’d have to ask a psychologist about that,’ he says. ‘There’s no satisfactory response to that question. I think there are things in the genes, and that your environment and experience are going to forge your personality. But aggression is also linked to the endocrine system – in other words, to the production of certain hormones.’

Guimard agrees that Hinault appeared, from the very start of his career, even from his accounts of relishing fistfights during his schooldays, to be quite fearless. Moreover, he never came across as someone racked by doubt; he decided on a path, and then followed it. Could it be true that the Badger had no hang-ups, insecurities or complexes? Again, Guimard isn’t sure. ‘To say he had no complexes perhaps isn’t totally correct.’

Hinault’s ‘destructive rage’ – as Bernard Vallet referred to it – could, suggests Guimard, have been a front, an act. ‘His aggressiveness was maybe a response to a certain number of complexes, or a certain shyness. I’m almost tempted to say that someone who is serene, who is calm, doesn’t have this aggressiveness. Is aggressiveness not a mask for certain issues, for certain doubts? Is it something someone needs to put them in a kind of trance, this aggressiveness?’

Laughing, Guimard adds: ‘You know, you can tell the difference between a dog whose training has been all caresses and red meat, and one who’s been trained with a whip. Anyway, what we can certainly say is that all great champions have a thirst for dominance and, by obligation, a more or less externalised aggression. It’s an aggression, just underneath the surface, ready to be called upon when they’re in difficulty.’

Guimard pauses, considers and offers his conclusion: ‘I’ve never met a nice, kind, soft man who’s succeeded in sport, whether it be in rugby or in football or in cycling.’

—-

Slaying the Badger by Richard Moore (Yellow Jersey) is available now.

http://richardmoore.co

Twitter: @rbmoore73