VeloNation looks back at the career of one of the most enigmatic riders of the 1980’s, who sadly died today

Andy Warhol famously said that one day everybody would be famous for 15 minutes; Laurent Fignon was famous for 8 seconds.

Andy Warhol famously said that one day everybody would be famous for 15 minutes; Laurent Fignon was famous for 8 seconds.

8 seconds. So many people have their lives defined by one single moment. Laurent Fignon’s misfortune was to be the man that lost the closest Tour de France in history; surely one of the biggest injustices in cycling.

Legend has it that he was once recognised in the street and asked if he really was the guy who lost the Tour by 8 seconds; “Non monsieur,” was his typical direct reply. “I’m the guy who won it twice.”

There was so much more to Fignon’s career than that one narrow defeat.

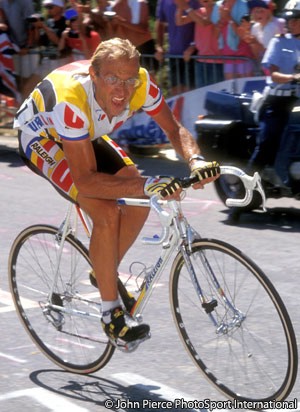

Fignon always stood out a little against the rest of the peloton. He earned his nickname “le Professeur” (which can either mean professor or teacher) partly from his characteristic wire-rim glasses, but also from the intellectual Parisien air that he exuded, which was in direct contrast to the rural Breton earthiness of his big rival Bernard “the Badger” Hinault.

An early start; a Tour winner at 22

An early start; a Tour winner at 22

In 1983 he started his first Tour de France with his Renault team captain Bernard Hinault, the defending champion and winner of four of the last five races, missing with a knee injury. The 22-year-old Parisien took the yellow jersey on stage 17 to Alpe d’Huez, after compatriot Pascal Simon abandoned with a broken shoulder. He increased his lead with victory in the penultimate stage time trial in Dijon and wore the yellow jersey into his home city the next day.

He was the second-youngest rider to win the Tour since World War Two; only the great Felice Gimondi had won it younger, some 18 years before. Nevertheless, everyone said, he only won because Hinault wasn’t there.

The next year Fignon rode the Giro d’Italia, coming close to emulating Hinault’s 1982 victory. Claims of organisational bias surround his narrow defeat to Italian favourite Francesco Moser. On the final time trial stage from Soave to the Roman Arena in Verona the TV helicopter flew between Moser and Fignon, who’d started last; its rotors allegedly creating a tailwind for the Italian and a headwind for the Frenchman.

Moser went on to win the race by 1’03” over Fignon.

Hinault returned to the Tour that year, now at the head of the La Vie Claire team and expecting to join Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx in the five-times club. Fignon, though, wearing the tricolore jersey of French champion, with the youthful World champion Greg LeMond by his side, beat the Badger by more than ten minutes.

Like Hinault though, Fignon was also plagued by knee problems and other injuries. The following two years’ Tours were characterised by the great battles between Hinault and LeMond; each of them taking a win apiece, with the races seemingly to themselves. Had Fignon been fit for either or both of these Tours, we would likely have seen a different picture.

Fast forward to 1989 then, to a France celebrating the two hundredth anniversary of its Revolution, a former champion returns from four injury ruined seasons in a bid to join the pantheon of three-time winners, in his home town; history demanded a Fignon victory.

The Parisien had already won the Giro d’Italia a month before, so was odds on favourite.

You know the rest.

That ’89 Tour that defines his legacy

That ’89 Tour that defines his legacy

LeMond, himself returning from years away from the top of the sport with rather more serious – life threatening in fact – shotgun injuries, had other ideas though. Famously introducing the technology of triathlon to the arcane world of cycling. The American won the first time trial of the race, 73km between Dinard and Rennes, to take the yellow jersey.

Fignon took it from him on the stage to Superbagnères in the Pyrénées, and importantly held it on July 14th, the French national holiday of which this was the bicentennial, before LeMond wrested it back the next day; in a time trial again.

On the stage to Alpe d’Huez, where he’d taken the first yellow jersey of his career six years earlier, Fignon retook the lead once more. He increased his lead the next day with a victory on the short stage from Bourg d’Oisans to Villard-de-Lans, but LeMond took some time back the next day on the road to Aix-les-Bains.

Nevertheless, on the final day Fignon had a 50 second lead over LeMond, with just 24.5km of flat roads between Louis XVI’s Palais de Versailles and the Champs-Elysées in Paris.

How much advantage LeMond’s revolutionary triathlon bars or aerodynamic helmet gave the American, and how much Fignon’s flapping ponytail slowed him down is a matter for debate. Chronic saddle sores, as well as fatigue from having won the Giro that year, doubtlessly played their part.

With the tailwind on his back though, LeMond beat Fignon into his hometown by 58 seconds, denying him – and France – a victory on the country’s biggest anniversary.

In addition to his two Tours de France and Giro d’Italia, Fignon also won the Criterium International, in 1982 and 1990, La Flèche Wallonne in 1986, and Milano-Sanremo in 1988 and 1989.

The nearest he came to the podium at the Tour again was 1991, when he finished sixth, 11’27” behind Miguel Indurain in the first of his five victories.

A post-racing career in race organisation and the media

A post-racing career in race organisation and the media

After retirement, Fignon became involved in the organisation of races, eventually taking ownership of the Paris-Nice race from the family of original organiser Jean Leulliot. Financial problems continued for the race though, and Fignon was forced to sell to Tour de France organiser ASO in 2002.

Never one to mince his words, Fignon was often called upon to comment on cycling, as well as commentate for French television. He famously refused to accept the excuse from French riders that their lack of results was due to “cyclisme a deux-vitesses” (cycling at two speeds) proclaiming that it was due to the lack of authority of director sportifs, and that French riders were too comfortable with their high salaries, not that all other nations’ riders were able to get away with doping.

Just before the 2009 Tour, Fignon announced to the world that he was suffering from cancer, which is now known to have started in his lungs. He simultaneously released his autobiography entitled “Nous étions jeunes et insouciants” (When we were young and carefree), in which he admitted using doping products during his career; while he admitted using products such as amphetamines and cocaine though, he denied using EPO, which is only rumoured to have hit the peloton towards the end of his career anyway.

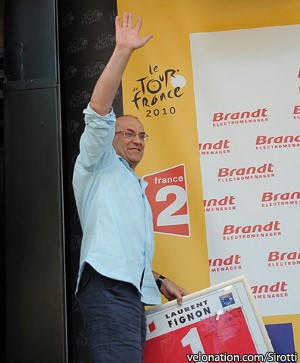

He continued to work with the French media, right up to last month’s Tour de France. Despite obviously suffering, more than anyone knew as it turned out, Fignon never made a big deal of the disease. On meeting old rival Hinault, who works for ASO (pictured above) the old Badger showed uncharacteristic emotion, perhaps knowing that it was the last time the two men would be together.